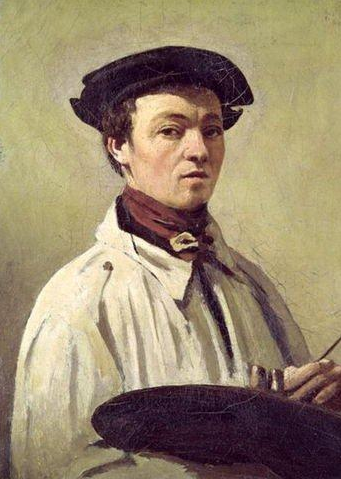

Jean Baptiste

Camille Corot

Biography

Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot was born on 16 July 1796 in Paris. His family was middle-class. Corot studied at boarding schools in Poissy and Rouen. He was an apprentice draper in Paris. Corot did not take to drapery and persuaded his father to subsidize his art studies in Paris.

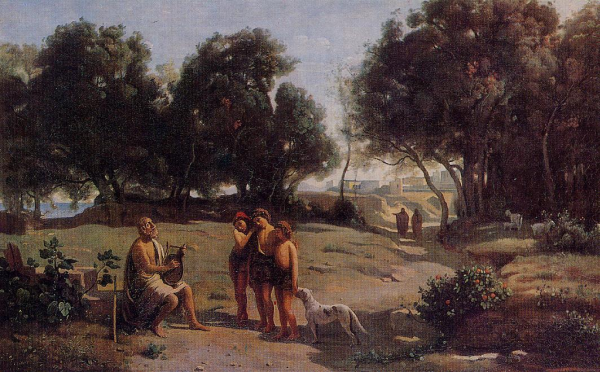

Corot started studying at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts, Paris in 1822. His instructors included artists who emphasized landscapes, most notably the printmaker and engraver Louis-François Bertin (1766-1841), and painter Michel Martin Michallon (1786-1851). Corot’s landscapes, however, were more influenced by Romantic landscape painters, in particular Claude Lorrain (1600-1682). Claude’s paintings are idealized landscapes but based on actual locations in France and Italy.

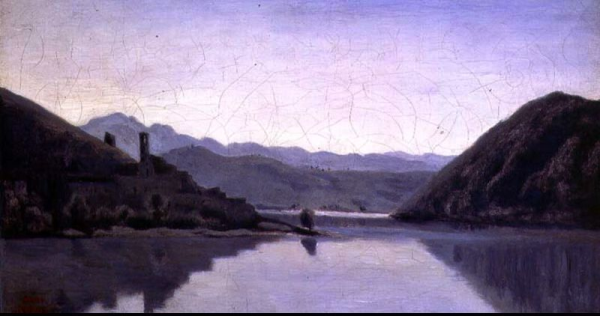

Corot’s travels to Italy strongly affected his art. Corot’s first trip to Italy was in 1825. Courlandais J.K. Baehr, an artist, went with him. Corot and Baehr were part of a group of foreign artists, followers of the XVIIth century masters, Poussin and Claude. (Corot’s first exhibit at the Paris Salon was in 1827.) In Rome, Corot studied the work of Guercino and Guido Reni. Corot traveled extensively in southern Italy. He made numerous oil sketches of the scenery, later developed into finished paintings in his studio. Corot stayed in Italy until 1828 during this first trip.

Corot’s second trip to Italy was in 1834. During this second visit, he focused his attention on Venice, making many oil sketches of its canals and buildings.

Corot’s third, and final, trip to Italy took place when he was nearly fifty years old. He traveled with Pierre Brizard (1737-1804) a painter. They stayed from 1843 to 1844. During this trip, Corot traveled in the north and made many oil sketches of Tivoli and Orvieto. He also went back to Venice.

In 1840, now a successful artist, he was awarded the French Cross of the Legion of Honor. He was elected an officer of the Legion of Honor in 1867.

Corot also traveled to Holland, Switzerland, and England. He traveled extensively in France between his first and last trips to Italy. During this time, he became associated with the Barbizon painters. In France, he made many oil sketches and finished paintings of the forest of Fontainebleau, Rouen, and Ville-d’Avray, west of Paris, where his family was based.

Corot was also an important teacher. His students included Camille Pissarro (1830-1903) and Eugéne Boudin (1824-1898).

He died at his family’s home in Ville-d’Avray on 22 February 1875.

Corot, La Cour d’une Maison de Payson, Normandy (ca. 1830-35) Museum of Fine Arts, Houston.

Corot, Italian Landscape (ca. 1835) oil on canvas, The Getty.

Corot, Macbeth, paysage (ca. 1858-1859) The Wallace Collection.

Corot, Ville-d’Avray (ca. 1860) oil on canvas, The Frick Collection.

Corot, The Pond (ca. 1868-70) oil on canvas, The Frick Collection.